Living with Loss: My Dear William's Birthday Reminder

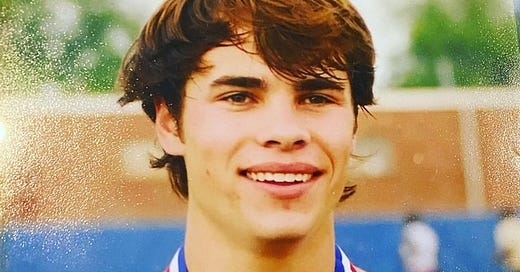

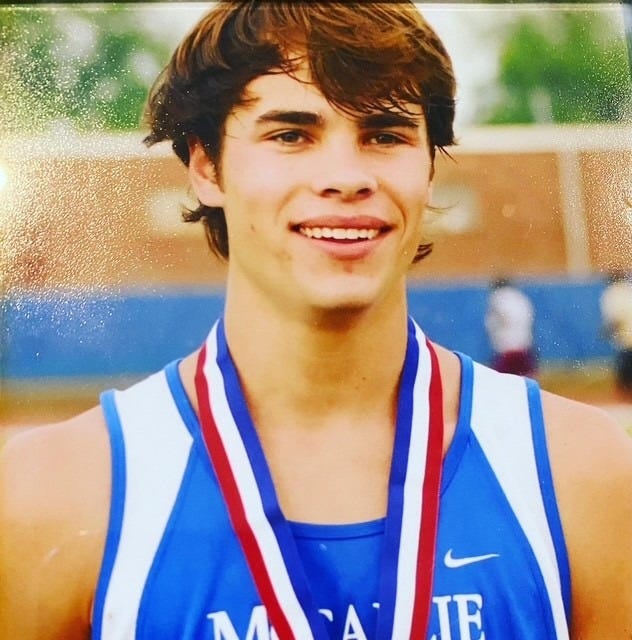

We speak our son's name, we celebrate his gift

The saying goes that the worst thing a parent can experience is the loss of a child.

You'll find no debate of the profound impact here.

My wife and I learned that lesson the hard way, joining the club that nobody wants entry when I found the oldest of our three dead at the age of 23 from an accidental drug overdose.

Our dear William would have turned 35 this month, and I remember like yesterday that January 1990 when the doctor placed him into my arms at six pounds, some odd ounces, and I pledged my eternal love.

As an adoptee who didn't know his biological roots then, William was the first blood relation I'd ever met.

And when William died, he was the first blood I'd ever known to say goodbye to.

It's been more than a decade since then—we're nearing the 12th anniversary—and the passage of time now gives us the gift of perspective on how the loss of our William has changed us and shaped us.

Here's what I know:

That day 35 years ago, when William was born, was the greatest gift.

That day I found him dead at the age of 23 was a loss and tragedy we'll feel for the rest of our lives. And yet in the years since, from that horrific loss, we have grown, for the better.

I am better today, in every well-being metric, than I was the day I found William dead, having taken his last breath alone hours before, as substances he abused stifled his breathing.

My family is better in every well-being metric it was the day I found William dead.

It's not his absence that has made the difference. Of course.

I so desperately wish he could have come along for our healing journey. He was trying and making progress in recovery, but relapse can happen with addiction, and these days, that comes with deadly risks.

I am stronger — we are stronger — because the death of someone close to us, a parent, a child, a spouse, or a friend or relative, presents as a defining moment for those of us remaining on earth.

It will make us or break us.

We decided.

Not to break.

We decided to mourn our dear William for as long as we lived and to also celebrate him for all that he gave us as a son and as a brother. We never stopped speaking his name, remembering how he made us laugh or talking with him, and I still hear him talking to me, his voice as a trusted angel of guidance.

We've done work to help others with addiction as he suffered, and that's made a difference, too -- for those we've been able to help, of course, but more for us.

Just last week, I got a thank you hug from a young woman who heard me speak on the Ole Miss campus at an educational event for new sorority members and reached out 48 hours later in a life-threatening condition asking for help. I helped get her into treatment within another 24 hours and heard from her periodically these last couple of years as she battled for sobriety. She returned to campus last week to resume her college career and invited me to meet for coffee.

"I would have died if not for you," she said.

"You would have died if not for my dear William," I told her, and she smiled with glistening eyes.

Her mother told me the young woman has a copy of my memoir Dear William, which she has carried around for two years, from treatment center to treatment center, as a security blanket.

"It arrived back here to Oxford with her," the mother said.

That book has been on quite a journey, according to the stories the young woman told me — one day, she can write her story of hard, to healing.

She told me that she's never read Dear William. It’s more, security blanket.

"I will read it," she said.

"Or not," I said. "As long as it keeps you."

The moving moment of a young person who responded to a talk or reading having actually read one of my books to get help and come back months later in gratitude wasn't my first — it's a miracle I never tire of.

Nor do I anticipate it being my last. Each of these moments, smiling, grateful faces, eyes locking directly with mine, is the greatest gift, a feeling not unlike when I first held my William that day, because, in a way, these moments allow me to go back to that joy, again. Like it was yesterday.

The passage of time can help us adjust to a significant loss, but it never erases it. Watching William's friends with families have children of their own and difference-making careers, their lives in full blossom, is heartwarming and heartbreaking. We get to celebrate them while simultaneously mourning what William never experienced.

But we have determined never to look away from those images. Even the hard is a hard worth feeling, a hard worth healing, because that's how we can live with loss, making what could be the most challenging thing a parent could ever experience manageable and, at times, immensely rewarding.

We miss our dear William so much—so very much. But he still gives us so much and also gives to others.

So we are living with the profound loss instead of making a parental proclamation of how it's the worst we could ever possibly experience.

Our son, as with the dearly departed angels of all, was a gift, and we cannot characterize anything related to his life, and passing, as the worst thing in our lives.

William’s death was a horrific tragedy. That we still mourn, and always will.

But we are thankful for the gift of parenthood, that he was our son. That he is our son, in life, and in death.